Barely good enough doesn't cut it

About a year ago Scott Ambler wrote an article stating, “One of Agile Modeling's more controversial concepts is the dictum that models and documents should be just barely good enough." Scott characterized barely good enough models as having just enough accuracy, consistency and detail to remain understandable and provide value and pointed out that barely good enough is context dependent—what’s good enough for your situation may not be barely good enough for mine.

I don’t like the words, “just barely good enough”. Even after a year, those four little words stick in my craw. I don’t scrape by on barely good enough planning or preparation in other aspects of my life. So why should that be the mantra for my modeling, design or design documentation activities? As a thought experiment, where would you mark a point on the hypothetical value per effort curve below that marks what you consider “just barely good just enough” modeling or design? Now place another mark for where you’d like to be on that value per effort curve for your current project.

I don’t want my checking account to have just barely enough money or get just barely good enough sleep. After a few weeks I’d be a walking zombie or the meanest bitch on the planet. If I allotted barely enough time to get to the airport, sooner or later I’d miss a flight. Since my local movie theatre is just 6 minutes from my door on a good traffic day, I do allot just barely enough time. Most of the time I make it to the movies. (I’m quite willing to trade off having to occasionally go to a later show against sitting through those annoying pre-movie ads.)

In most aspects of my personal and professional life I make choices about how much planning, preparation and cushion or slack I need based on my preferences, style, and the consequences of failure. When things matter I take extra care. When they don’t, well…I’m as casual as the next person. But I prefer to think that I take adequate measures most of the time—adequate and good enough. Not just barely good enough. To me this subtle shift in attitude and outlook is huge. And an appropriate one for agile developers to take.

Barely good enough thinking can too easily be used as an excuse for taking the easier, inadequate way out. Sure, we can discuss what’s “barely good enough” but that missing the point—don’t we all want to do adequate, good work, and not do things that aren’t needed? Barely good enough thinking will always make us question whether we’ve done too much. And as a consequence, any design before coding is getting a bad rap.

I propose we get rid of that barely scraping by attitude and replace it with a healthier one. I propose we start using words like “enough”, “adequate”, or “meets the project’s needs” to describe how much design we do. Or perhaps “just enough” modeling as Susan Burk described in her Practical Process talk at SD Best Practices. These words are far less edgy. But that is a good thing. Without feeling desperate, I’m hopeful people can feel safe enough to start having meaningful conversation about what’s enough given their current situation.

Scott’s edgy phrase emphasizes the point that agilists’ strive to minimize unnecessary work. Design just in time. Do just enough. Don’t go overboard. Push towards minimizing if you’ve had a tendency to over design or document. But I say do an adequate job. Meet your objectives. Maybe you need to do even more designing than you have been doing. Nothing edgy about that message, just common sense.

The “just barely good enough” message can be a real turn off to teams who come from traditions of producing high-quality, high value designs. What? You mean to be agile I should turn away from what I find to be valuable? No, you don’t.

Adequate design means you may need to sort through options and gain enough understanding before you pound out much production code. You may even need to design and build a few prototypes to understand the problem before you launch into something. That’s OK if that's what you need to do. You can be agile without having to barely scrape by. In fact, conscientious developers know that and insist on taking whatever measures they need to build the right stuff.

I have known agile teams who feel guilty about taking any time to model and explore their design options. And they feel inadequate when they find it useful to write down a simple use case to clarify a story card. Good grief! Clarity is what we're after. Others feel not clever (or edgy enough) when they need to think about their problem or sketch out a potential design before writing tests or code. I say stop feeling guilty! If writing, thinking, and talking about your design with others helps you clarify your ideas—keep it up. Most people need to think a bit before they code.

If you want to keep permanent representations of key design or architectural views in addition to their code don’t feel guilty about that either. It just means that you find value in more than simply the working code. (If you don’t, then stop it!) The right kind of adequate design documentation can go a long ways in communicating key ideas to new team members, support and operations. Your code doesn’t always speak clearly to others about your design.

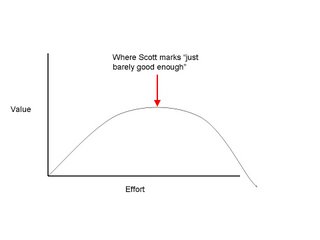

At Software Development Best Practices, Scott gave a talk on agile modeling where explained that barely good enough was the point where the value per effort is maximized. His point on his hypothetical curve is way higher than where I’d mark it. I’m betting your sense of what’s barely good enough differs from Scott’s view, too. I’d label Scott’s point as “optimal” and mark just barely good enough way to the left.

I’m not sure what an ideal value/effort distribution curve looks like, and I suspect a value per effort curve will vary by project type and organization. I’m skeptical that it looks anything like the curve Scott drew (Scott, doesn’t make any claims that he’s discovered a ideal shape for this curve—only that you should find the “barely good enough point” and not overdo design). Curious about various distribution curves and their properties, I took a look on wikipedia. Nothing seemed to fit my expectations. I would suspect that the value of design gradually tails off rather than steeply declines (on most projects). Have you found the value/effort for modeling to follow a normal distribution curve or some other known distribution function? Have you it to vary by project type? If so, in what ways? Do you find that value to decay at some point (after hitting some maximal value per effort point)? Or have you found it to remain steady or keep increasing at a slower rate? I’d be interested in your thoughts.

I don’t like the words, “just barely good enough”. Even after a year, those four little words stick in my craw. I don’t scrape by on barely good enough planning or preparation in other aspects of my life. So why should that be the mantra for my modeling, design or design documentation activities? As a thought experiment, where would you mark a point on the hypothetical value per effort curve below that marks what you consider “just barely good just enough” modeling or design? Now place another mark for where you’d like to be on that value per effort curve for your current project.

I don’t want my checking account to have just barely enough money or get just barely good enough sleep. After a few weeks I’d be a walking zombie or the meanest bitch on the planet. If I allotted barely enough time to get to the airport, sooner or later I’d miss a flight. Since my local movie theatre is just 6 minutes from my door on a good traffic day, I do allot just barely enough time. Most of the time I make it to the movies. (I’m quite willing to trade off having to occasionally go to a later show against sitting through those annoying pre-movie ads.)

In most aspects of my personal and professional life I make choices about how much planning, preparation and cushion or slack I need based on my preferences, style, and the consequences of failure. When things matter I take extra care. When they don’t, well…I’m as casual as the next person. But I prefer to think that I take adequate measures most of the time—adequate and good enough. Not just barely good enough. To me this subtle shift in attitude and outlook is huge. And an appropriate one for agile developers to take.

Barely good enough thinking can too easily be used as an excuse for taking the easier, inadequate way out. Sure, we can discuss what’s “barely good enough” but that missing the point—don’t we all want to do adequate, good work, and not do things that aren’t needed? Barely good enough thinking will always make us question whether we’ve done too much. And as a consequence, any design before coding is getting a bad rap.

I propose we get rid of that barely scraping by attitude and replace it with a healthier one. I propose we start using words like “enough”, “adequate”, or “meets the project’s needs” to describe how much design we do. Or perhaps “just enough” modeling as Susan Burk described in her Practical Process talk at SD Best Practices. These words are far less edgy. But that is a good thing. Without feeling desperate, I’m hopeful people can feel safe enough to start having meaningful conversation about what’s enough given their current situation.

Scott’s edgy phrase emphasizes the point that agilists’ strive to minimize unnecessary work. Design just in time. Do just enough. Don’t go overboard. Push towards minimizing if you’ve had a tendency to over design or document. But I say do an adequate job. Meet your objectives. Maybe you need to do even more designing than you have been doing. Nothing edgy about that message, just common sense.

The “just barely good enough” message can be a real turn off to teams who come from traditions of producing high-quality, high value designs. What? You mean to be agile I should turn away from what I find to be valuable? No, you don’t.

Adequate design means you may need to sort through options and gain enough understanding before you pound out much production code. You may even need to design and build a few prototypes to understand the problem before you launch into something. That’s OK if that's what you need to do. You can be agile without having to barely scrape by. In fact, conscientious developers know that and insist on taking whatever measures they need to build the right stuff.

I have known agile teams who feel guilty about taking any time to model and explore their design options. And they feel inadequate when they find it useful to write down a simple use case to clarify a story card. Good grief! Clarity is what we're after. Others feel not clever (or edgy enough) when they need to think about their problem or sketch out a potential design before writing tests or code. I say stop feeling guilty! If writing, thinking, and talking about your design with others helps you clarify your ideas—keep it up. Most people need to think a bit before they code.

If you want to keep permanent representations of key design or architectural views in addition to their code don’t feel guilty about that either. It just means that you find value in more than simply the working code. (If you don’t, then stop it!) The right kind of adequate design documentation can go a long ways in communicating key ideas to new team members, support and operations. Your code doesn’t always speak clearly to others about your design.

At Software Development Best Practices, Scott gave a talk on agile modeling where explained that barely good enough was the point where the value per effort is maximized. His point on his hypothetical curve is way higher than where I’d mark it. I’m betting your sense of what’s barely good enough differs from Scott’s view, too. I’d label Scott’s point as “optimal” and mark just barely good enough way to the left.

I’m not sure what an ideal value/effort distribution curve looks like, and I suspect a value per effort curve will vary by project type and organization. I’m skeptical that it looks anything like the curve Scott drew (Scott, doesn’t make any claims that he’s discovered a ideal shape for this curve—only that you should find the “barely good enough point” and not overdo design). Curious about various distribution curves and their properties, I took a look on wikipedia. Nothing seemed to fit my expectations. I would suspect that the value of design gradually tails off rather than steeply declines (on most projects). Have you found the value/effort for modeling to follow a normal distribution curve or some other known distribution function? Have you it to vary by project type? If so, in what ways? Do you find that value to decay at some point (after hitting some maximal value per effort point)? Or have you found it to remain steady or keep increasing at a slower rate? I’d be interested in your thoughts.

5 Comments:

I'm going to disagree for two reasons. The two reasons may not be entirely unrelated, and I don't think they are serious disgreements, more a matter of emphasis.

First, if we find we haven't done enough modelling it should be easy to do a bit more. If we find we've done more than necessary that extra effort cannot be recouped.

This does somewhat depend on the assumption that there is little or no overhead on 'doing more later' over and above the overhead for doing it all at once.

Second, I take the view that the model that really matters is the model a person has in his mind. All other models exist only to get the right model into the right mind at the right time.

The implication is that as soon as the right model is in the right mind, we can stop modelling. Any extra modelling is superfluous. What we have at that point is 'enough'; and if we stop right at that point it is 'barely enough'.

I agree that we could improve the wording; "just enough" would work for me.

Can we recognise when we have got the right model into the right mind? I think so. At that point, the person is off and running on her own.

Mostly I agree with you: the attitude or the emphasize is at least wrong.

I would like to turn your curve up-side-down and talk about abstraction level of the model. In this case the x –axis is the level of abstraction and y –axis the relative complexity of the model. Here at least the shape of your curve is right. Starting with very low abstraction level our complexity equals the total complexity of realty. By lifting abstraction level we simplify the model and thus the complexity starts to come down.

When our level of abstraction have reached the level where we have purified most unessential features we have reached a model that describes the most essential structure and behaviour of the domain and at the same time does this in an abstract way. This is the point at the bottom of the curve and is at relative the complexity minimum.

Abstract behaviour mean actually most economically distributed responsibilities ( I would like to call that ideal distribution). This seldom is close or equal to the corresponding behaviour of the realty. I find this part most difficult.

IF one continues to lift the level of abstraction further the model get more and more simple but of course we start to hide essential structures inside single model elements and the model is easy to understand but at the same this is of less and less value.

I have created abstract domain OO-model like this for 10 years now. We have worked with business people and from scratch. It has always work fine. Actually a modeller can always decide in advance the level abstraction of the model. My practical experience keeps me trying to achieve to level of 30 – 60 classes, but in some case we have not bee able to do under 100.

I have written a short example of abstraction levels:

http://www.kolumbus.fi/tamminen.jukka/objects/DomainApproach.htm

and a complexity measure:

http://www.kolumbus.fi/tamminen.jukka/objects/COmplexityMeasure.htm

I'm reminded of Colin Chapman's famous view that a Grand Prix car should win the race and as it crossed the finishline it should collapse in a heap of bits. If it didn't do that, it was built too strongly.

P.

It might actually be a good idea to look at what I wrote at http://www.agilemodeling.com/essays/barelyGoodEnough.html .

I'm pretty clear, as Paul indicates, that if a model isn't adequate then you should address whatever issues are making it inadequate.

Also, comparisons to arriving for flights really aren't fair. Barely good enough is in the eye of the beholder. If that means for you that you arrive 30 minutes before a flight then so be it. If it means arriving 3 hours before a flight, that's OK too. If it means arriving 3 minutes before a flight (yikes) then I guess that also works for you. You need to adjust accordingly for your situation, there's no one exact answer.

The curve that I present is a fairly standard economic one. If something isn't good enough, then you should be able to invest more effort in it and get more value from it. If it's already good enough then you're obviously wasting your investment. Obviously this is an ideal curve, you could easily invest more effort in something, completely mess it up, and get no extra value. So in practice, your mileage is going to vary.

What Rebecca is describing as adequate is exactly the sorts of ideas that are promoted at www.agilemodeling.com. If it's not adequate, then clearly it isn't good enough, isn't it?

- Scott

Although some of these terms have some "emotional" baggage associated with them, I do believe having terms to define key points on the graph is useful.

Personally, I would define two key points, the first at the beginning of the plateau in value (i.e. within a certain range of the maximum) and the second at the end of the plateau (within a certain range of the maximum before the value tapers off too much).

I believe "just barely good enough" correspond to the first point, and, I would suggest, most modellers keep on modelling until the second point.

In this regard, I think being "just barely good enough" is an important concept. It demonstrates we don't get much more value (sometimes no extra value, i.e. at the right-hand point) for quite a bit more (wasted) effort.

I would prefer a better term though - perhaps something like "least mostly effective effort" (most people would probably be happy with doing the least amount of work to get mostly the best result).

Regards,

Ashley.

--

Ashley Aitken

Perth, Western Australia

mrhatken at mac dot com

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home